If I ever win the lottery, I will fill my place with classic paintings by my favorite artists-Rembrandt, Vermeer, Monet, Titian- a dreamy aspiration shared by many around the globe. A fortunate few, and I mean both figuratively and literally, are actually able to realize this dream. In fact, some of the world’s most valuable art is owned by such moguls, like the famous Paul Cézanne painting The Card Players, sold to the Royal Family of Qatar at a jaw-dropping cost of $250 million to $300 million, or artist Willem Kooning’s Woman III, purchased by the American Hedge Fund manager, Steven Cohen, for an astounding $137.5 million, or Francis Bacon’s Triptych, bought by the Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich for $86.4 million. Even the fictional magnate Gail Wynard from The Fountainhead had his very own walk-in gallery of exquisite art right in his home- his authentic refuge from an artificial world.

Aside from the obvious monetary and investment values of these paintings, there is a more intangible value to art, almost spiritual in nature that unites us all. People from all socio-economic backgrounds, ages, nationalities, spend hours appreciating, creating, buying, discussing, and promoting art. Governments dedicate time and resources on setting up departments of art and culture, aimed at promoting and protecting art (sadly even destroying art incompatible with their ideologies). In fact, some of a child’s first modes of communication include not words, but art in the form of colors, drawings, objects, songs. Moreover, studying art alone can potentially reveal the entire history and evolution of mankind; from the first cave paintings in Spain etched on rock 40,000 years ago, to Rembrandt’s Anatomy lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp from 1632, to the contemporary Obama murals by anonymous artists, adorning the dilapidated walls of Brooklyn.

Could the experience of looking at art be similar to meditation? A chance to be alone with your mind, a moment for introspection, to focus on just one thing—not on the echoing of Om— but on the vivid colors and textures of a painting, or the intricate carvings on a delicate porcelain vase– and channel your senses in a single direction to experience one’s own version of peace, love, or pleasure. Several scientific studies have used modern techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (a technique that measures brain activity based on corresponding changes in blood flow) of the brain to reveal temporary and permanent effects from meditation on the brain. Do similar effects occur through thorough imbuement of the brain by art?

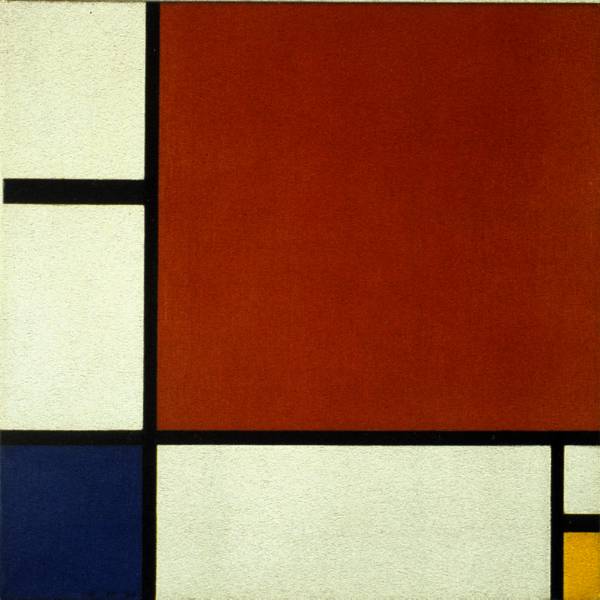

Other scientifically interesting questions arising from this prevalent and timeless phenomenon of art are: How does the brain process art? What about art gives us pleasure worth spending our limited time and money? In short, why do we, as a species, look at art? Is it because other, seemingly knowledgeable experts tell us that it’s something worth looking at? Would Van Gogh’s vase of twelve sunflowers be just an ordinary painting if it didn’t come with the brand name? Or do we just like looking at beautiful things (although plenty of famous art isn’t exactly beautiful)? This fundamental human behavior has given rise to a burgeoning discipline of neuroscience: neuroaesthetics: a discipline dedicated to understanding the neurological basis of aesthetic experiences,

Using modern techniques and tools, scientists are working to understand why and how we look at art. For example, fMRI techniques can be used to determine the ways our brain activity changes in response to looking at art. Van Gogh’s paintings, as one study shows, activate the MT+ region of the brain (responsible for deciphering object locations), evoking a sense of movement in the viewer. Another study reveals that facial portraits activate a different region of the brain, when compared to landscape paintings. Moreover, beautiful faces activate the fusiform face region (responsible for facial recognition) and its adjacent areas, a neural activity that seems to increase with the beauty of an art piece*.

Neuroaesthetics studies have also provided insights into factors that influence our perception of art. For example, when labeled as belonging to a museum, an art piece receives better rating by its viewers, and greater neural activity is observed in certain areas of their brains. Moreover, different areas of the brain are activated in response to viewing an original masterpiece, or a copy* .

Another intriguing area of investigation is understanding the paradox of how certain neurological diseases enhance the artistic capabilities of patients, often allowing them to produce “realistic, obsessive, and detailed” art. Interestingly, some autistic individuals, given their characteristic obsessive-compulsive traits, arealso predisposed to producing amazing art*.

It seems that when it comes to appreciating art, or even producing it, we rely on a combination of our built-in biology, as well as the experiences and environmental cues that influence our everyday experiences from the moment we are born. Thus, understanding why we look at art, can potentially enhance our understanding of complex concepts concerning human behavior, such as “mate selection, consumer behavior, and communication.” Because even a mere still life can set into motion a surge of activity in the intricate neural circuitry of our complex brains.

* Chatterjee and Vartanian (2014) Trends in Cognitive Science.